Review by Michelanne Forster…

The desire to understand who you are and how you are connected to your ancestors seems to grow stronger with age. These universal feelings cut across cultures and historical events but for those of us who belong to the second generation, as I do, locating people, places, historical records or even family photos, can be a monumental task. Whatever we manage to retrieve from the past is often fragmented, distorted, or suffused withpain. We have been severed by the Holocaust yet are still linked to it.

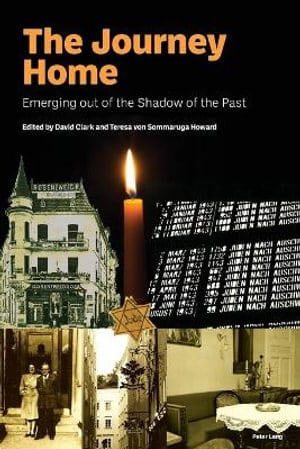

The Journey Home – Emerging out of the Shadows of the Past, edited by David Clark and Teresa von Sommaruga Howard, traces physical and emotional journeys undertaken by the children of Holocaust survivors or refugees-the “second generation”- who try to make sense out of the genocide that killed six million.

What, then, triggers these second generation journeys to the homelands and dwelling places of our parents and relatives? The editors offer the idea that a journey may start with the death of a loved one, or a significant illness. Sometimes motivation comes from wanting to explore “Jewish roots” and what it means to be Jewish. Or it may simply come upon us as an elemental urge to go “home” – whatever that contested word means.

Thus, we set off in hope that the materiality of actual streets, buildings, fields and forests will help us overcome the gaps in our knowledge and the holes in our hearts. Armed with maps, research notes

and foreign currency we are looking for some kind of memorialization or even healing. In striving to know what often cannot be known, we overcome geographical dislocation, language barriers and lack of cultural or historical knowledge.

Yet, as the poet and essayist Diti Ronen writes in her essay, The only house that was built for me, ‘retrospective introspection’ is an endless journey, a cycle that ‘cannot be closed.’

Still, we journey.

Part One offers stories of travel undertaken with a survivor or refugee parent. We go with Janet Eisenstein and her mother to Berlin, with Naomi Levy and her mother to Krakow, with Tina Kennedy and her father to Vienna. Other writers take us to Bratislava and Poland or again, to Berlin.

What most interested me in this section of the book was the way in which parent/child relationships coped and changed as a result of these journeys into the past. In ‘Heimish’at Last, Eisenstein’s mother makes it clear she doesn’t even like thinking about Berlin, yet there they go, mother and daughter together, to Berlin’s Jewish memorial sites on a sponsored trip by the Association of Jewish Refugees.

Eisenstein sees that there are two conflicting perspectives: her mother looks for “rosy moments”, while she is dwells on “potent history.” What a complicated and fascinating set of metaphysical baggage this is to carry! In contrast, in Krakow, a visit with my mother to her hometown, Naomi Levy tells us how her relationship with her mother “blossomed” during their joint research projects.

She reflects that their journey led “paradoxically to greater individuality and a finding of… our separate voices (43)”. I was drawn to Tina Kennedy’s account of her return to Vienna with her once idolized father as it best reflected my own uneasy story. In her essay, Kennedy confesses that her journey “blew apart the fantasy and revealed to me that this storyline no longer supported me in adulthood, even though I had needed it in childhood (51).

Gaining understanding and acceptance of our parents’ reality from an adult perspective is a theme of many successful holocaust memoirs, such as Maus, or The Lost: A Search for Six of Six Million. The generational insights offered in the first section of The Journey Home are readable and sympathetic.

Part Two features journeys undertaken alone, sans parent or survivor relatives. Rosemary Schonfeld writes in Terezín 2000 that her aim is to give the Holocaust contemporary relevance, while Marian Liebmann writes in Exploring German Jewish Roots in Berlin that her numerous visits to this city connected her to her heritage and gave her a feeling of “belonging to a family that I never met” (132).

[PHOTO: Co-editor Teresa von Sommaruga Howard is a member of the Auckland second generation group.]

I was especially interested in the essays by Oliver Hoffmann and Diana Wichtel, both Kiwis whom I know as members of a second generation group in Auckland, New Zealand.

Oliver’s parents left Germany in 1938. His Jewish mother and a non-Jewish father were both members of a Jewish resistance group which was part of an opposition Communist Party (KPO), but the Nuremberg laws prevented their marriage until they were able to escape to London, on their way to New Zealand via Canada. Like many of the second generation, Hoffman explains he grew up with a minimum understanding of Jewish culture and German history, yet he lived and worked in Berlin for over twenty years in search of a history that he felt was “pre-ordained” for himself (144).

Wichtel’s story, told in full in her book Driving to Treblinka A Long Search for a Lost Father (2017) was well received in Aotearoa/New Zealand. She writes about being envious of those able to go back to Europe with their parents because this could never be her experience. In unravelling themystery of her father’s life, Wichtel was able to find what was “precious” and “restorative” in it, and cement a lifelong relationship with him, even in his absence. I found this a moving and profound declaration. Certainly,all the eighteen contributions in this book show us, in one way or another, that the strength of familial ties survives absence and the wish to forget or repress memory.

The Journey Home offers a balanced view of the lived experience of memorialization, and current thinking about appropriate Holocaust commemoration.

In Part Three, which is devoted to journeys undertaken to attend commemorative events, the writer Marilyn Moos tells us about her experience of Denk Mal Am Ort (Memorial on Site) celebrations. This idea came out of a Dutch scheme in 2012 and was introduced in Berlin in 2016.

In visiting the places where her parents and relatives once lived, Moos mulls over the long-term effects of Nazism. She could have been a German ‘maiden’, instead she’s a visitor to the homes where her family once lived. The Munich house of her ersatz grandfather Herman, who died in Theresienstadt, is beautifully described as “a run-down multi-occupied wreck,” smelling of “dampened decay”. In a small act of resistance, Moos tells us how she covertly put her parents’ ashes into flower beds, flowerpots, bushes and trees, then threw the last bits into the winds over Berlin (221).

These actions within the framework of an official remembrance occasion affirmed, for me, the value of individual stories. No government-sanctioned event could compete with Moos’s description of her personal sorrow and chutzpah.

The concentrated effort and perseverance of the second generation writers whom we come to know in The Journey Home, is inspiring. Written during the Covid-19 pandemic, the book is meticulously laid out, offers useful photographs, a comprehensive bibliography, and an informative introduction and epilogue. On reading the book I was reassured that the first generation’s understandable silence, evasion, confusion, loss of memory and death cannot, and will not, end their stories.

– Michelanne Forster

————————————————————————————————– —————————————